Constrained Optimisation

When I first learned machine learning, I was scared by the complicated formulas. I spent much time going over subjects like Linear Algebra and Calculus since I’d already forgotten them. But with time, I feel more and more confident in understanding them, though they sometimes still confuse me. Anyway, in my opinion, there is no need to know every detail about each equation, after all, we are not mathematicians. Instead, learning how to use these math formulas to solve real-world problems is the key.

As we all know, the main effort in machine learning is to find a loss function and optimise it, i.e. find the minimum or maximum point, and this is the question of optimisation. However, we may only find local optimisation because of some constraints. Even without constraints, there is still a chance that we would reach local optimisation only. In short, there are two main situations we need to consider: unconstrained optimisation and constrained optimisation. And constrained optimisation further falls into two categories, equality constraints or inequality constraints.

On the other hand, the extreme value of a function typically relates to some property of that function. That means if we know a function has some particular property, then we know that it must have an extreme value or not. This property can be characterised by convexity. As you can see, this post will be very mathematical. Seems a bit scary, ummm…

Equality Constraints

Suppose we want to minimise a function $f(x)$ subject to an equality constraint, $g(x) = 0$. This can be solved by introducing Lagrange multiplier $\alpha$

$$ \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) = f(x) - \alpha g(x) $$

Then set the gradient of $\mathcal{L}$ equal to the zero vector

$$ \nabla_x \mathcal{L} = \nabla_x f(x) - \alpha \nabla_xg(x) = 0 $$

$$ \frac{\partial \mathcal L}{\partial \alpha} = -g(x) = 0 $$

Finally, solving the above equations will give us the minimum point we are seeking.

Multiple Constraints

If we have multiple constraints, then multiple Lagrange multipliers are introduced,

$$ \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) = f(x) - \sum_i^m \alpha_i g_i(x) $$ And the corresponding solutions are given by,

$$ \nabla_x f(x) = \sum_i^m \alpha_i \nabla_xg_i(x) $$

$$ \frac{\partial \mathcal L}{\partial \alpha_i} = -g_i(x) = 0 $$

Lagrange

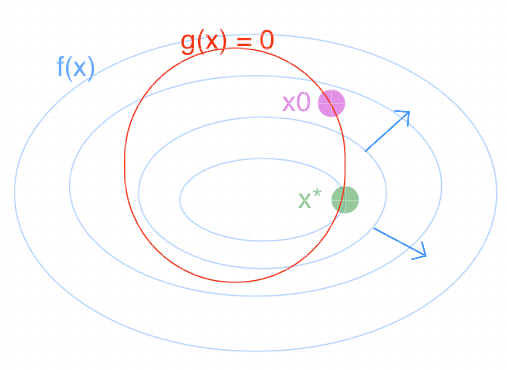

But what’s the rationale behind these formulas? Though we are not required to know everything, basic understanding of Lagrange is still needed. Remember that the question is to find a point $x^*$ that satisfies both $g(x^*) = 0$ and $f(x^*) =m $, where $m$ is the minimum value of $f(x)$ given the constraint.

The line represented by $f(x) = c$ is known as a contour line. Since $f(x)$ can have many values, we can plot many contour lines with equal intervals between lines in ascending or descending order from inner to outer. Graphically, we want to find a point that lies on the line of $g(x) = 0$ and the line of $f(x)$ with the minimum value simultaneously as shown in Figure 1. The green point is the point we are looking for.

But we still need to figure out equations to calculate the position of the gree point. Let’s start from $x_0$, the magenta point in Figure 1. Mathematically, the above process of finding $x^*$ can be described as follows,

$$ f(x_0 + \delta x) < f(x_0) $$

$$ g(x_0) = g(x_0 + \delta x) = 0 $$

So in which direction should we move at $x_0$? With the aid of Taylor expansion, we have $$ g(x_0 + \delta x) = g(x_1) = g(x_0) + (x_1 - x_0)^T\nabla_xg(x_0) + \frac{1}{2} (x_1 - x_0)^T H (x_1 - x_0) $$

$$ = g(x_0) + (x_1 - x_0)^T\nabla_xg(x_0) + O(||x_1 - x_0||^2) $$

where $x_1 = x_0 + \delta x$ and $H$ is a matrix of second derivative of $g(x)$ known as Hessian. The third term tends to be zero if $\delta x$ is small enough, then we are left with

$$ g(x_0 + \delta x) = g(x_0) + (x_1 - x_0)^T\nabla_xg(x_0) = g(x_0) $$

Thus,

$$ (x_1 - x_0)^T\nabla_xg(x_0) = 0 $$

which means that the moving direction from $x_0$ should be perpedicular to $\nabla_xg(x_0)$. But we are not done, because not all $(\delta x = x_1 - x_0)$ point to the right direction along which $f(x)$ decreases. In order to ensure this, we require that $\delta x$ must satisfy

$$ (x_1 - x_0)^T ( - \nabla_x f(x)) > 0 $$

where $- \nabla_x f(x)$ indicates the descent direction. Therefore, as long as the value of the dot product is greater than zero, the moving of point will continue unless the value becomes zero. If so, it means that the direction of $\nabla_x f(x)$ is parallel to $\nabla_x g(x)$, i.e.

$$ -\nabla_x f(x) = \lambda \nabla_x g(x) $$

We can rewrite this by replacing $\lambda$ with $\alpha = -\lambda $

$$ \nabla_x f(x) = \alpha \nabla_x g(x) $$

Finally, we come to the method of Lagrange multipliers.

Inequality Constraints

Now we consider another situation where we have inequality constraints, i.e. $g(x) \ge 0$. It looks a little complicated, but if we think about it for a while, we can find that only two things could happen, as shown in Figure 2,

- either the optimum point satisfies $g(x) \gt 0$ or

- the (local) optimum point lies on the boundary, $g(x) = 0$

Again, we use Lagrange to solve it,

$$ \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) = f(x) - \alpha g(x) $$

Case 1

In the first case where the optimum point lies in the interior of the constraint, i.e. $g(x) > 0$, which is filled in red in Figure 2 a). We set $\alpha = 0$, which means the constrains has no influence on $f(x)$.

Case 2

As for the second case, it is exactly the same as the equality constraints, i.e.

$$ \nabla_x f(x) = \alpha \nabla_xg(x) $$

but with an additional constraint $\alpha > 0$. So why do we set $\alpha > 0$ here?

$\alpha \ge 0$

Visually, it can be seen From Figure 2 b) that both the magenta and blue points seem to be the right point we are seeking. But in fact, only the bule one is in a lower position. And we find that $\nabla_x f(x) $ and $\nabla_x g(x)$ point to the same direction at the blue point. Thus, $\alpha$ is positive.

In theory, if we are at a point where $-\nabla_x f(x)$ points to the feasible region, which is the area defined by $g(x) > 0$, i.e. any value of $x$ inside this region is valid, it means that a point with a smaller value of $f(x)$ could be found in the feasible region. But it contradicts the assumption that we can only move along the boundary of the region. In other words, this is not the optimal point.

If $-\nabla_x f(x)$ at some point points to the exterior of the feasible region, then we are in the right position because the outer of the feasible region is invalid and we cannot move forward any further(we are already on the border of the region).

It is noticeable that $\nabla_x g(x)$ points in towards the feasible region. Therefore, we conclude that $\nabla_x f(x)$ and $\nabla_x g(x)$ have the same direction. Thus, $\alpha$ is positive.

From above, we can also draw another conclusion shown below

$$ \alpha g(x) = 0 $$

KKT Conditions

Putting it together, we want to minimise $f(x)$ subject $g(x) \ge 0$, and the Lagrangian function is defined as follows,

$$ \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) = f(x) - \alpha g(x) $$

Then we can find a local mininum $x^*$ s.t.

- $\nabla_x f(x) = \alpha \nabla_xg(x)$

- $\alpha \ge 0$

- $\alpha = 0$, the solution is in the interior or

- $\alpha \gt 0$ and $g(x) = 0$, i.e. the solution is on the boundary

- $\alpha g(x) = 0$

These are the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions.

Many Inequalities

Once again, if we have many ineuqality constraints, then Lagrangian function is given by,

$$ \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) = f(x) - \sum_i^m \alpha_i g_i(x) $$

And the corresponding solutions are given by,

$$ \nabla_x f(x) = \sum_i^m \alpha_i \nabla_xg_i(x) $$

plus the constraints that

- either $\alpha_i = 0$ or

- $\alpha_i \gt 0$ and $g_i(x) = 0$

- $\alpha_i \nabla_x g_i(x) = 0$

Duality

Let’s revisit the above problem again. Consider minimising a function $f(x)$ subject to $g(x) \ge 0$, the lagrangian function is given by

$$ \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) = f(x) - \alpha g(x) $$

Primal Problem

Now consider maximising $\mathcal{L}(x, \alpha)$ w.r.t $\alpha$,

$$ \text{max}_\alpha \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) = \begin{cases} f(x) & \text{if $g(x) \ge 0$} \\ \infin & \text{otherwise}\end{cases} $$

-

For any $x'$ that satisfies the constraint $g(x) \ge 0$, we conclude that

$$ f(x') \ge \mathcal{L}(x', \alpha) $$

i.e. the upper bound of $\mathcal{L}(x, \alpha)$ is $f(x)$. Thus, the maximum value of $\mathcal{L}$ we can obtain is to set $\alpha = 0$

-

On the contratry, if the constraint is not satisfied, then there exists some $x'$ that satisfies $g(x) \lt 0$. If so, then we can make $\mathcal{L}$ infinite by taking $\alpha \rarr \infin$.

Next we take the minimum of the maximum of $\mathcal{L}$, i.e.

$$ \text{min}_\text{x} \text{max}_\alpha \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) $$

which is equivalent to the problem of minimising $f(x)$ subject to $g(x) \ge 0$. We call the original problem as primal problem.

Dual Problem

Yet we still don’t find a solution to $x$. How about reversing the order of max and min like the below formula?

$$ \text{max}_\alpha \text{min}_\text{x} \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) $$

We solve $\text{min}_\text{x} \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha)$ using the method of Lagrange, and find that $x$ is a function of $\alpha$. Then we plug $x$ into $ \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha)$ and obtain a new function of $\alpha$, say $h(\alpha)$. So the problem becomes to maximise $h(\alpha$), also known as dual problem,

$$ \text{max}_\alpha h(\alpha) $$

However, is the solution to dual problem the same as the primal problem? Why do we bother solving a dual problem rather than the original problem?

Since $\alpha \ge 0$ and $g(x) \ge 0$, we have,

$$ \text{min}_\text{x} \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) \le \text{min}_x f(x) = p^* $$

$$ d^* = \text{max}_\alpha \text{min}_\text{x} \mathcal{L}(x, \alpha) \le p^* $$

where $p^*$ and $d^*$ are the optima of the primal and dual problem respectively.

It can be seen that the solution of dual problem gives us a lower bound on the primal problem. If possible, we can also have the same solution.

The reason why we solve the dual problem is that the primal problem works in a feature space that may have high dimensions while the dual problems depends on the number of constraints, which is much smaller than the dimensitionality of $x$.

Linear Programming

In linear programming, we minimise a linear function $c^Tx$ subject to a series of linear constraints $g(x) = Mx - b \ge 0$. The primal problem is described as follows,

$$ \mathcal{L} (x, \alpha) = c^Tx - \alpha^T(Mx - b) $$

$$ \text{minimise } c^T x $$

$$ \text{subject to } Mx \ge b $$

and the dual problem is defined as,

$$ \mathcal{L} (x, \alpha) = b^T\alpha - x^T(M^T \alpha - c) $$

$$ \text{maximise } b^T \alpha $$

$$ \text{subject to } M^T \alpha\le c $$

Let’s see and example.

Primal problem

$$ \text{minimise } z = 15x_1 + 12x_2\\ \text{subject to } x_1 + 2x_2 \ge 3, 2x_1 - 4 x_2 \ge 5 $$

Dual problem

$$ \text{maximise } w = 3y_1 + 5y_2\\ \text{subject to } y_1 + 2y_2 \le 15, 2y_1 - 4 y_2 \le 12 $$

Quadratic Programming

In quadratic programming, we minimise a quadratic function $x^TQx$ subject to a series of linear constraints $g(x) = Mx - b \ge 0$. The primal problem is described as follows,

$$ \text{max}_\alpha \text{min}_\text{x} \mathcal{L} (x, \alpha) = x^TQx - \alpha^T(Mx - b) $$

Using the method of Lagrange, we have $x^* = \frac{1}{2}Q^{-1}M^T\alpha$, and we substitue it into $\mathcal{L}$

$$ \text{max}_\alpha -\frac{1}{4} \alpha^TMQ^{-1}M^T\alpha + \alpha^Tb $$

Convexity

Quadratic Form

Quadratic form is a polynominal function with terms all of degree of two. For example, $4x^2 + 2xy - 3y^2$. — Wikipedia

Here “the degree of two” means that the sum of exponents for each term is 2. A general quadratic form of $n$ variables is defined below, where $M$ could be chosen symmetric.

$$ Q(\bold x) = \bold x^T \bold M \bold x = \sum_{i,j}^d \bold M_{ij} \bold x_i \bold x_j $$

In this example $4x^2 + 2xy - 3y^2$, the quadratic form is given by,

$$ Q(\bold x) = \bold x^TM\bold x = \displaystyle{\begin{bmatrix}x&y\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}4&1\\1&-3 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\end{bmatrix} } $$

Basically, quadratic form is a mapping from $R^d$ to $R$. Without doubtness, for any quadratic form, we have $Q(\bold 0) = 0$. But is $x=\bold 0$ is the minimum or maximum point for $Q$ ? The answer is determined by the definiteness of $Q$ described below,

- $Q(\bold x) \gt0$,

- positive definite

- $Q(\bold x) \ge 0$,

- positive semi-definite

- $Q(\bold x) \lt 0$ ,

- negative definite

- $Q(\bold x) \le 0$,

- negative semi-definite

- $Q(\bold x)$ could be both positive and negative

- indefinite

Clearly,

- if $Q$ is positive definite, then $x = 0$ is global minimum

- if $Q$ is negative definite, then $x = 0$ is global maximum

Furthermore, quadratic form can also be characterised in terms of eigenvalues:

- positive definite if and only if the eigenvalues of $M$ are positive,

- negative definite if and only if the eigenvalues of $M$ are negative,

- indefinite if and only if $M$ has bothe positive and negative eigenvalues

Here are some proofs. First, we should know that any two eigenvectors from different eigenspaces of a symmetric matrix are orthogonal and any symmetric matrix can be orthogonally diagonalizable.

Let $\bold P = [\bold v1, \bold v2, …, \bold v_n]$ be eigenvectors that correspond to different eigenvalues $\Lambda= \lambda_1, \lambda_2, …, \lambda_n$ of a symmetric matrix $A$. To show that $v_1 \cdot v_2 = 0$, compute

$$ \lambda_1 v_1 \cdot v_2 = (A v_1)^T v_2 = v_1^T A v_2 = \lambda_2 v_1^Tv_2 $$

$$ (\lambda_1 - \lambda_2) v_1^T v_2 = 0 $$

But $ \lambda_1 \ne \lambda_2$, so $v1 \cdot v2=0$. Furthermore, $\bold P ^T \bold P = I$, so $P^{-1} = P^T$. Then we have

$$ AP = PD\\A = PDP^{-1} = PDP^T $$

The quadratic form of $A$ can be written as follows,

$$ x^T A x= x^T PDP^Tx = (P^Tx)^T D (P^Tx) = y^TDy = \lambda_1y_1^2 + \lambda_2y_2^2 + … + \lambda_ny_n^2 $$

If the eigenvalues of $A$ are positive, then $x^TAx > 0$ and $A$ is positive definite. On the other hand, if $A$ is positive definite, then $x^TAx > 0$ for any $x \ne 0$. If we substitute $x$ with an eigenvector $v_1$, we have

$$ v_1^T A v_1 = v_1^T \lambda v_1 = \lambda v_1^Tv_1 = \lambda ||v_1||^2 \gt 0 $$

Thus, $\lambda > 0$.

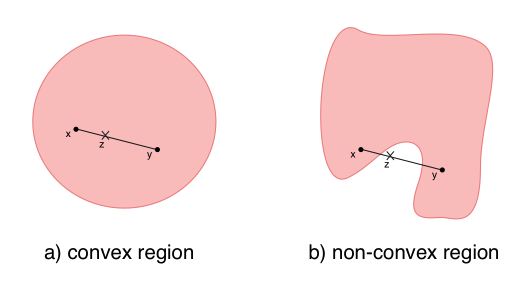

Convex Region

Before we talk about convex function, let’s start with convex region and convex set.

A region $R$ is said to be a convex region if any two points $x$ and $y$ in that region plus any $a \in [0, 1]$ satisfy,

$$ z = a x + ( 1 - a )y \in R $$

Convex Set

Similarly, for any set of points $S$, if for any two points $x, y \in S$ and any $a \in [0, 1]$ satisfy $$ z = a x + ( 1 - a )y \in S $$ then $S$ is a convex set. We can prove that the set of positive semi-definite matrices form a convex set. Let $A_1, A_2 \in S$, compute

$$ x^T z x = x^T (a A_1 + ( 1 - a)A_2)x = x^TaA_1x + x^T ( 1-a) A_2 x \ge 0 $$

Thus, $z$ is positive semi-definite and $z \in S$.

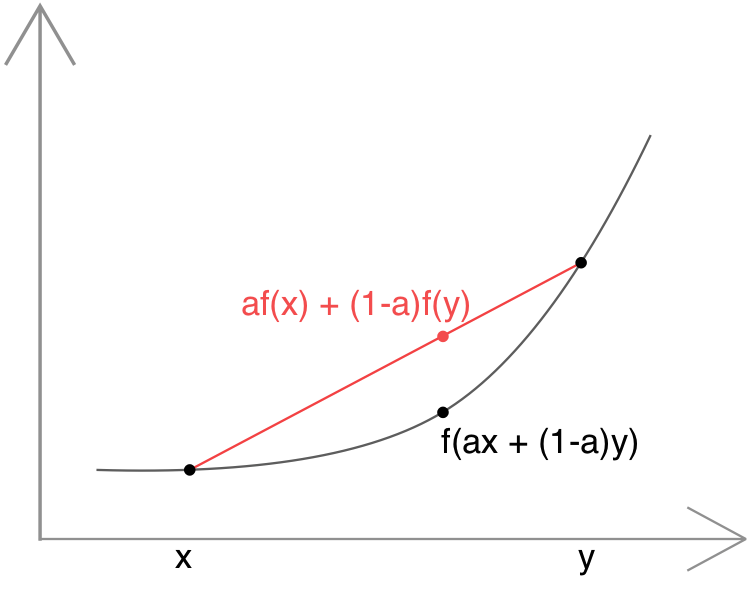

Convex Function

Any function is said to be convex if any two points $x$ and $y$ plus $a \in [0, 1]$ satisfy

$$ af(x) + (1 - a) f(y) \ge f(a x + (1 -a ) y) $$

Conversely, if the condition doesn’t meet, the function then is said to be a convex-down or concave function. These two functions are symmetric — everything true for convex functions is also true for concave functions.

At the beginning, I often mixed up them. I couldn’t tell which figure is convex or concave. But later, I found a simple way to distinguish them correctly. First we find the lowest point or the highest point of a figure. Then we observe the direction along which the curve expands. If the direction is toward down, the function is concave. Otherwise, it’s convex. By the way, the area enclosed by the curve (lies on or above the curve ) is defined as epigraph. The epigraph of a convex function forms a convex region, and if the epigraph of a function forms a convex region then the function is convex.

Linear Functions

Now let’s take a look at a special case — equality. A function that we are quite familar with satisfies the equality, which is linear function.

$$ f(x) = mx + c $$ It’s easy to proove it.

$$ m(ax + (1 - a)y) + c = max + my - may + c = af(x) - ac + my(1 -a) + c \\= af(x) + my(1-a) + c(1-a) = af(x) + (1-a)f(y) $$

So is it a convex or concave function? The answer is both.

Strictly Convex

What about the condition without euqality? Well, such a condition is called strict inequality and functions that satisfy the strict inequality is said to be strictly convex/concave.

Sums of Convex functions

If we have a set of convex functions, then it’s easy to prove that the sum of the multiplication of positive factors and these functions is also a convex function using the property that the second derivative is equal or greater than zero. Below is the proof.

$$ g(x) = \sum_i \alpha_i f_i(x) $$

$$ g''(x) = \sum_i \alpha_i f''_i(x) \ge 0 $$

Second derivative

One thing we should remember is that any tangent line of a convex funtion lies on or below the function. Let $t, z$ be two points on the graph of a convex function, then we can derive the following conditions,

- $ t \lt z$

$$ f(t) + f'(t) (z - t)\le f(z) $$

$$ f'(t) \le \frac{f(z) - f(t)}{z - t} $$

- $ t \gt z$

$$ f(t) - f'(t)(t - z) \le f(z) $$

$$ \frac{f(t) - f(z)}{(t - z)} \le f'(t) $$

The two conditions can be combined as a single condition for any two points $a, b$ that satisfies $a < b$ as follows,

$$ f'(a) \le \frac{f(a) - f(b)}{b-a} \le f'(b) $$

Hence, $f''(a) \ge 0$.

In high dimension, the second derivative of a function is known as Hessian. And a necessary and sufficient condition for that function to be convex is that its Hesssian must be positive semi-positive at all points.

Unique Minimum

As said early, convexity can help to find the extreme value of a function. How does it work? Let $x^*$ be a local minimum of a function, suppose there exists another points $\hat x$ such that $f(\hat x) < f(x^*)$. By the definition of convexity, we have

$$ f(a \hat x + (1-a)x^*) \le af(\hat x) + (1-a) f(x^*) \le af(x^*) + (1-a) f(x^*) = f(x^*) $$

If we set $ a \rarr 0 $, it means that there exist points around $x^*$ with a smaller value than $f(x*)$, which is a contradiction to the definition of local minimum.

Thus, we can see that any local minimum of a convex funtion is a global minimum. Besides,

- there could be many local minimum for a convex function. In other words, the minimum of a convex function will form a convex set.

- a strictly convex function has at most one global minimum

Putting it together, the whole process of determining whether a function would have a minimum is shown in Figure 5

Inverse of Convex Funtions

Let $f(x)$ be a convex function, how about the convexity of the inverse of it, i.e. $g(x) = f^{-1}(x)$?

First, the second derivative of a composite function is given by

$$ \frac{d^2f(g(x))}{dx^2} = \frac{d f'(g(x)) g'(x)}{dx} = f''(g(x)) [g'(x)]^2 + f'(x) g''(x) $$

Besides, if $f^{-1}(x)$ is the invese of $(x)$, we have

$$ f(f^{-1}(x)) = x $$

$$ f''(f^{-1}(x)) = 0 $$

Thus, we conclude that

$$ g''(x) = - \frac{f''(g(x)) [g'(x)]^2}{f'(g(x))} $$

Since $f''(x) \ge 0$ and $[g'(x)]^2 \ge 0$, the sign of $g''(x)$ is determined by $-f'(g(x))$.

Here is an example. Let $f(x) = x^2$ , so that $f''(x) = 2 \gt 0$ and $f'(x) = 2x$. Since $g(y) = f^{-1}(y) = \sqrt y \ge 0$, $f'(g(x)) \ge 0$ and consequently $\sqrt x$ is concave.

Jensen’s inequality

Jensen’s inequality involves inequality of convex function, which states that for any convex function $f(x)$,

$$ E[f(x)] \ge f(E[x]) $$

and for any concave function,

$$ E[f(x)] \le f(E[x]) $$

It’s easy to prove using the fact that a convex function must lie on or above its tangent line at any point $x'$

$$ f(\hat x) \ge f(x') + (\hat x - x')^T \nabla f(x) $$

so this is true for $x' = E[x]$

$$ f(\hat x) \ge f(E[x]) + (\hat x - E[x])^T \nabla f(x) $$

then taking expectations of both sides

$$ E[f(\hat x)] \ge f(E[x]) + (E[\hat x] - E[x])^T \nabla f(x) = f(E[x]) $$

A typical example is $f(x) = x^2$, Jensen’s inequality shows that

$$ E[x^2] - E^2[x] \ge 0 $$

Well, it’s the formula of variance, and variance are non-negative.

Conclusion

Finally, we’re here. I spent several days writing up this article. To be honest, I am not a math person, and it was a struggle to explain these mathematical concepts and formulas clearly and accurately. But in doing so, I had a better understanding about optimisation. But knowing these equations only is not enough, the key point is to learn to apply them in machine learning to solve real-world problems. Anyway, we are done for now.