Optimization

We’ve talked about many ML algorithms and DL architectures so far, but how to find the optimal parameters? Mathematically, the process of minimizing the objective functions is called optimization, but it’s a bit different in DL — the global minimum point does not always achieve the best generalization performance. After all, we are minimizing the training error. Besides, the loss function typically is very complex, and there is no analytical solution to it. In this case, we have only one choice — optimization algorithms.

Newton’s Method

Bascially, Newton’s method is a root-finding method, for example, the root of $f(x) = x^2 - 8$. Assuming that we start from the point $x_0$, and the intersection of the tangent line and the x-axis is the point $(x_1, 0)$, then we have

$$ \hat f(x_1) = f(x_0) + (x_1 - x_0) f'(x_0) $$

let $\hat f(x_1)=0$,

$$ x_1 = x_0 - \frac{ f(x_0)}{f'(x_0)} $$

We can repeat this operation starting from $x_1$ until we think the precision is sufficient. Typically, we generalize these steps as follows,

$$ x_{n+1} = x_n - \frac{f(x_n)}{f'(x_n)} $$ Let’s start from $x_0 = 4$, the results are shown below. We see that $x_3$ is very close to the actual value $2\sqrt2$, so we can stop.

x_0 =4

x_1 = 3

x_2 = 2.833333

x_3 = 2.828431

The above linear approximation holds when $x_1 - x_0$ is really small. For a larger $x_1-x_0$, we can use the second-order taylor expression. Recall that Taylor expanding around $x^*$ is

$$ f(x) = f(x^*) + (x - x^*)f'(x^*) + \frac{1}{2}(x-x^*)^2f''(x^*) + … $$ If $x - x^*$ is sufficiently small, the higher order terms are ignored. The derivative of $f(x)$ w.r.t $x - x^*$ is $$ f'(x^*) + (x - x^*)f''(x^*) = 0 $$

Thus,

$$ x = x^* - \frac{f'(x^*)}{f''(x^*)} $$

High Dimension

For high dimension, the Taylor expansion at $\bold x_0$ is

$$ f(\bold x) = f(\bold x_0) + (\bold x - \bold x_0)^T \nabla f(\bold x_0) + \frac{1}{2} (\bold x - \bold x_0)^T H (\bold x - \bold x_0) + … $$ where $H$ is the Hessian matrix with elements $$ H_{ij} = \frac{\partial^2 f(\bold x_0)}{\partial x_i \partial x_j} $$ So, the minimum point can be found at

$$ \bold x = \bold x^* - H^{-1} \nabla f(x^* ) $$

Pros and Cons

- Efficient when we are close to the minimum.

- Computing Hessian matrix is time-consuming, $O(N^2)$

- Liable to arrive at saddle points

- Loss would increase for nonconvex problems because Hessian would be negative

- take absolute value

- change learning rate

Gradient Descent

Intuition

Suppose $x-x^* = \eta f'(x^*)$ and $\eta>0$ is small enough, based on the first order Taylor expansion, we obtain

$$ f(x^* - \eta f'(x^*)) = f(x^*) - \eta f'^2(x^*) \le f(x^*) $$ This means the loss would decrease when we move againt the direction of gradient. $$ x \larr x - \eta f'(x) $$ Pros and cons

- large learning rating would osillate; small and we make slow progress

- GD would get stuck at a local minimum

Batch

It’s vanilla gradient descent, which computes the gradient for all the training dataset. $$ \theta = \theta - \eta \cdot \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{|D|} \nabla_\theta J(\theta, x_i, y_i) $$

Stochastic

SGD updates parameters for each example, so it has a high variance in the change in parameter values. $$ \theta = \theta - \eta \cdot \nabla_\theta J( \theta; x_i; y_i) $$

Mini-batch

Mini-batch updates parameters for a small batch of training data. $$ \theta = \theta - \eta \cdot \frac{1}{|B|} \sum_{i=1}^{|B|} \nabla_\theta J(\theta, x_i, y_i) $$

- reduce variance of the parameter updates and lead to stable convergence

- add noise (stochasic) as we are sampling data (might help escape local-minima)

- taking many smaller steps of gradients reduces likelihood of divergence

- make use of the matrix optimization

- Typically, mini-batch size is the power of $2$, like 64, 128, 256

Dynamic Learning Rate

Replacing $\eta$ with a time-dependent $\eta$

- piecewise constant

$$ \eta(t) = \eta_i \text{ if } t_i \le t \le t_{i+1} $$

- exponential decay

$$ \eta(t) = \eta_0 e^{\lambda t} $$

- polynomial decay $$ \eta(t) = \eta_0 (\beta t + 1)^{-\alpha} $$

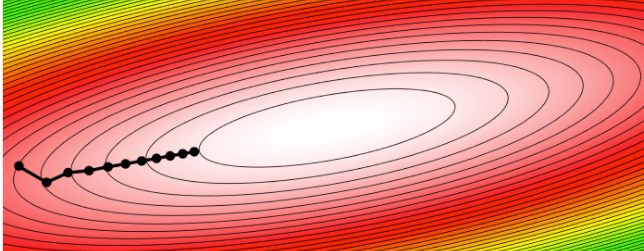

Momentum

One problem with SGD is that it could take much time if the shape of loss function is anisotropic, as shown in Figure 1. This is because we are moving along the direction of gradient, but it doesn’t point to the mnimum. In other words, in high dimension, we zig zag

- stepping consistently in directions with low curvature

- jumping backwards and forwards past the minimum in directions with high curvature

Momentum is a method to increase steps in low curvature directions and decrease it in high curvature directions by adding the gradients of the past steps to the current gradient. $\beta$ is usually set to $0.9$.

$$ v_{t+1} = \beta v_t + g_t \\ \theta = \theta - \eta \cdot v_{t+1} $$

Exponentially weighted average

$$ v_{t} = \beta v_{t-1} + (1 - \beta) g_t $$ correct bias

$$ v_{t} = \frac{v_t}{1-\beta^t} $$

The exponentially weighted average allows us to obtain the average over a range of days ($\frac{1}{1-\beta}$) without explicitly storing the data of these data and calculting the numerical average.

In the case of gradient, $v_t$ tells us the weighted average of the past $\frac{1}{1-\beta}$ gradients. Thus, a large $\beta$ will lead to a smooth change due to a long-range average.

AdaGrad

The idea of learning rate decay is to decrease learning rate as the learning progresses, but different parameters have different gradient. We cannot reduce learning rate in the same level for all parameters. Instead, it would be better to adapt the learning rate to the parameters.

AdaGrad is such a method that perform smaller updates for frequent updated parameters and large updates for less frequent updates parameters by accumulating the square of the gradients of the past steps.

$$ h \larr h + g\odot g \\ \bold w \larr \bold w - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{h + \epsilon}} \odot g $$ Pros and Cons

- it will shink the learning rate and no longer update at some point

RMSProp

$$ h \larr \beta h + (1 - \beta) g\odot g \\ \bold w \larr \bold w - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{h + \epsilon}} \odot g $$

$\beta$ is usually set to $0.9$ and $\eta$ is $0.001$.

Adam

Adam combines momentum and RMSprop to compute the adaptive learning rate.

$$ m_t = \beta_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) g_t \\ h_t = \beta_2 h_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_2) g_t \odot g_t \\ \theta \larr \theta - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{h_t} + \epsilon} m_t $$