Probabilistic Model

The goal of machine learning is to infer an unknown pattern from data. However, both parameters and predictions are estimated values, so how confident are we in these values? To measure uncertainty, we use probability. On the other hand, Bayes' theorem provides a framework for us to invert the problem into a forward process, where we observe data from parameters instead of making inferences from data.

Probability

Random Variable

At the beginning, let’s have a quick refresh on probability.

A random variable is variable that can take on different values randomly.

On its own, it is a description the states that are possible; it must be coupled with a probability distribution that specifies how likely each of these states are.

— Deep Learning, p54

In short, a random variable covers two aspects: possible value and the likelihood of taking that value. Conventionly, we use a capital letter, such as $X$ or $Y$, to represent a random variable.

Conditional Probability

Suppose we have two random variables of interest, $X$ and $Y$,

-

The joint probability of $X$ that takes the value of $x$ and $Y$ that takes the value of $y$ is written as $P(X = x, Y=y)$, which means that the probability of $x$ and $y$ happening at the same time

-

Given $Y=y$, the conditional probability of $X$ given $Y=y$ is denoted by $P(X|Y=y)$

There are two major rules of probability that we should remember,

- the sum rule, i.e. the marginal probability of $X$ that takes the value of $x$, irrespective of the value of $Y$

$$ P(X=x) = \sum_{y \in Y} P(X=x, Y=y) $$

- the product rule, i.e. the joint probability of $X$ and $Y$ can be written as the product of the conditional probability and the marginal probability

$$ P(X, Y) = P(Y|X) P(X) = P(X|Y)P(Y) $$

From the above formula, we can deduce the following equation, which is also known as Bayes' Rule,

$$ P(Y|X) = \frac{P(X|Y)P(Y)}{P(X)} $$

Expectation

The expectation of the function $f(x)$ of a random variable $x$ is the mean value of $f(x)$

$$ E_{x \sim P(x) } f(x) = \sum_x P(x) f(x) $$

The variance measures how much a new sample drawn from $P(x)$ deviate from the mean value

$$ \text{Var(x)} = E[ (f(x) - E[f(x)])^2 ] $$

Bayes' Inference

In machine learning, our goal is to learn a model $\Theta$ from a given data set $D$, but $\Theta$ is uncertain. One way to measure uncertainty is probability, so the question becomes how to compute the probablity of $\Theta$ given the data $D$, i.e. $P(\Theta|D)$. But the only thing we know is the observed data, so how can we do it? The answer is the Bayes' Rule, which helps us convert this into a forward problem, where parameters are known and thus we can draw data from the distribution determined by that paramaters. The formula is defined as follows,

$$ P(\Theta|D) = \frac{P(D|\Theta)P(\Theta)}{P(D)} $$

- $P(\Theta)$ is called the prior probability, i.e. the best guess about $\Theta$ before we see the data. You might have a good estimate on it or simply have no idea at all

- $P(D|\Theta)$ is the likelihood of the data given the parameters $\Theta$

- $P(D)$ is the evidence or marginal probability denoted by $P(D) = \sum_{\theta \in \Theta }P(D, \theta)$

- $P(\Theta|D)$ is the posterior probability, i.e. the updated probability of $\theta_i$ after we see the data

Pros and cons

Pros

- Bayes' rule provides us a full probabilistic description of the parameters

- It doesn’t overfit since we are not choosing the best parameters that fit the data perfectly

Cons

- However, we need to compute $P(D)$, whichsometimes is not reasonable, e.g. there are too many possible values of $\Theta$

- Posterior might not be described as a nice probability function

MAP

If we ignore the evidence $P(D)$ (after all, it’s just a constant for any $\theta$), we are only left with the numerator. An easy way to compute $P(\Theta|D$) is to find the maximum value shown below, though it’s not a strictly probability

$$ {\argmax}_{\Theta} log (P(D|\Theta)) + log (P(\Theta)) $$

This method is called Maximum A Posterior(MAP). However, it can overfit because we are finding the parameters that maximise the likelihood of the observed data. Thus, we are likely to get a model that fit the data with no errors.

MLE

Furthermore, if we ignore the prior $P(\Theta)$, the MAP is just maximising the likelihood(MLE), which is widely used statistics in machine learning.

Conjugate Prior

In some cases, the likelihood of the observed data $D$ is simple to compute, and the posterior would have the same form as the prior if we could find a right prior. Such a likelihood and prior distribution are said to be ‘conjugate’. Here we consider two common distributions that a prior might follow: Bernoulli and Poisson.

Bernoulli Distribution

Suppose we have a binary random variable $X \in \{0, 1 \}$, and $X_i=1$ if the ith trial is a head and 0 otherwise. Then the likelihood of $X_i$ given the probability of a head $\mu$ is

$$ P(X_i = 1|\mu) = \mu $$

$$ P(X_i = 0|\mu) = 1 - \mu $$

Or we can write it in this form

$$ P(X_i|\mu) = \mu^{X_i} (1-\mu)^{1-X_i} $$

Suppose we have a data set $ D = \{ x_1, x_2, …, x_n \}$, where $x_i \in \{0, 1 \}$, assuming these observations are drawn independently, then the likelihood of $D$ can be computed as follows,

$$ L(D;\mu) = \prod_{i=1}^N P(X_i|\mu) = \prod_{i=1}^N \mu^{X_i} (1-\mu)^{1-X_i} = \mu^{N_h} (1-\mu)^{N-N_h} $$ where $N_h = \sum_i X_i$, i.e number of heads.

Beta

The next step is to choose the prior $P(\Theta)$. In the case of Bernoulli, it would be better if we can find a function that has a simliar exponential parts that appeared in the above likelihood function to model the probability of every single value of $\mu$. Luckily, Beta distribution shown below is the right function we are looking for.

$$ P(\mu) = Beta(\mu|a, b) = \frac{\mu^{a-1} (1-\mu)^{b-1}}{B(a, b)} $$

where $B(a, b)$ is a normalisation constant

$$ B(a, b) = \int_0^1 \mu^{a-1} (1-\mu)^{b-1} d\mu $$

So how to choose a, b? It depends. If we have no idea about $\mu$, it’s natural to assume that there are equal chances to take all vaules of $\mu$. This corresponds to a beta distribution with $a = b = 1$.

The last step is to plug the prior and likelihood into the Bayes' rules,

$$ P(\mu|D) = \frac{P(D|\mu)P(\mu)}{P(D)} = \frac{\mu^{N_h} (1-\mu)^{N-N_h} \mu^{a-1} (1-\mu)^{b-1}}{P(D) B(a, b)} = \frac{\mu^{N_h+a-1} (1-\mu)^{N+b-N_h-1}}{P(D) B(a, b)} $$

and

$$ P(D) = \int_0^1 \frac{\mu^{N_h+a-1} (1-\mu)^{N+b-N_h-1}} {B(a, b)} d\mu = \frac{B(N_h +a, N+b-N_h)}{B(a, b)} $$

So we have

$$ P(\mu|D) = Beta(\mu| N_h + a, N+b-N_h) $$

In summary, before we see data, we have some beliefs about $\mu$ governed by $Beta(\mu|a, b)$. After seeing the data, the probability of $\mu$ now is updated via $Beta(\mu| N_h + a, N+b-N_h)$, which can be served as the prior for the next new observations.

Incremental Updating

For independent data we can update the hyperparamters incrementally, we consider an individual data at a time so that,

$$ P(\mu|X_1) = \frac{P(X_1|\mu)P(\mu)}{P(X_1)} $$

$$ P(\mu|X_2, X_1) = \frac{P(X_2, X_1|\mu)P(\mu)}{P(X_2, X_1)} = \frac{P(X_2|\mu)P(X_1|\mu)P(\mu)}{P(X_2)P(X_1)} = \frac{P(X_2|\mu)P(\mu|X_1)}{P(X_2)} $$

It’s clear that the previous posterior now becomes the prior for the next piece of data.

Poisson Distribution

Poisson distribution measures the probability of a given number of events occuring in a specific time range, which is given by,

$$ Pois(N;\theta) = \frac{e^{-\theta}\theta^N}{N!} $$

where $N$ is the number of occurences in a time slot and $\theta$ is the parameter of interest. For example, we want to know the rate of traffic along a road between 8am and 9am, so $N$ is the number of cars and $\mu$ is the rate of traffic per hour.

Gamma

Then we have Gamma distribution as our prior,

$$ P(\theta) = \Gamma(\theta|a, b) = \frac{b^a \theta^{a-1} e^{-b\theta}}{\Gamma(a)} $$

so the posterior after seeing the first piece of data is

$$ P(\theta|N_1) = \frac{P(N_1|\theta)P(\theta)}{P(N_1)} = \frac{b^a}{\Gamma(a) N_1! P(N_1) }e^{-(b+1)\theta} \theta^{N+a-1} \propto e^{-(b+1)\theta} \theta^{N_1+a-1} $$

we can see that the posterior is also a Gamma distribution with $a_1 = a + N_1$ and $b_1 = b + 1$.

Multinominal Distribution

In the case of Bernoulli, we only consider two outcomes: 0 or 1. But what if we have 3 or more outcomes? Well, we use multinominal distribution, which is the generalization of the binominal distribution. Suppose we have a $k$-sided dice with the probability of $\mu_k$ for $x^k = 1$, and we roll the dice $N$ times, so there are $N$ independent observations $x_1, x_2, …, x_n$, the multinominal distribution are given by,

$$ M(m_1, m_2, …, m_k|\mu, N) = \frac{N!}{m_1!m_2!…m_k!} \prod_{k=1}^K \mu_k^{m_k} $$

where $m_k=\sum_n^Nx_n^k$ represents the number of $x_n^k = 1$.

Dirichlet

TODO

Gaussian Distribution

In the case of a single variable $x$, the Gaussian distribution is defined as,

$$ N(x|\mu, \sigma^2) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}}e^{-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}(x-\mu)^2} $$

For a vector-valued random variable $\bold x \in R^d$ , We can extend it to the Multivariate Gaussian distribution

$$ N(\bold x|\mu, \sigma^2) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{(2\pi)^d}\sigma_1\sigma_2…\sigma_d} e^{\frac{1}{-2{\sigma_1}^2}(x_1 - \mu_1)^2 + \frac{1}{-2{\sigma_2}^2}(x_2 - \mu_2)^2 + … + \frac{1}{-2{\sigma_d}^2}(x_d - \mu_d)^2} $$

The exponential part of $e$ can be re-written in a matrix form, as shown below, where

$$ \begin{bmatrix} x_1 &x_2 & … & x_d \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_1^2 \\ & \sigma_2^2 & \\ & … \\ & & \sigma_d^2 \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\x_2 \\ … \\ x_d \end{bmatrix} \\ = (x - \mu)^T {\sum}^{-1}(x-\mu) $$

Thus,

$$ N(\bold x; \mu, \sum) = \frac{1}{\sqrt {(2 \pi)^d |\sum}|} e^{-\frac{1}{2} (x - \mu)^T\sum^{-1}(x-\mu)} $$

The number of free parameters

A general symmetric covariance matrix has $ 1 + 2 + 3 + … + D = D(D+1)/2$ independent parameters, and there are another $D$ independent parameters in $\mu$ , giving $D(D+3)/2$ parameters in total.

If we consider diagonal covariance matrix $\sum = diag(\sigma_i^2)$, then we have a total of $D + D = 2D$ independent parameters.

If we restrict the covariance matrix to be proportional to the identity matrix, $\sum=\sigma^2I$, giving $D + 1 $ independent parameters, in this case, the $PDF$ is $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}^D\sigma^D} e^{\frac{1}{-2{\sigma}^2}\sum_{i=1}^D(x_i - \mu_i)^2}$, which means the density is only related to the distance to the mean from the $x$ (different $x$ with the same distance to the mean has equal density)

Maximum likelihood Estimate

Given a data set $\bold X = (\bold x_1 , . . . , \bold x_N )^T $ in which the observations ${ x_n }$ are assumed to be drawn independently from a multivariate Gaussian distribution,

Esimation for $\mu$

Step 1: construct the likelihood function $$ L(\mu,\sum|D) = \prod_{i=1}^N N(\mu, \sum) $$

Step 2: The log likelihood function is given by $$ \text{In} L = \sum_{i=1}^N {\frac{-D}{2} \text{In}2\pi - \frac{1}{2} \text{In}\sum - \frac{1}{2}(x_i-\mu)^T{\sum}^{-1} (x_i-\mu)} $$

Step 3: the derivative of the log likelihood with respect to $\mu$ is given by

$$ \frac{ \partial L }{\partial \mu} = \sum_{i=1}^N{\sum}^{-1}(x_i - \mu) $$ Here, we use a bit trick

$$ x^TMx = 2Mx $$ Since the element of $\sum^{-1}$ is positive,we have

$$ \mu_{ML} = \frac{1}{N} \sum^Nx_n $$

Estimation for $\Sigma^{-1}$

$$ trace[ABC] = trace[BAC] = trace[CAB] \\ x^TAx = tr[x^TAx] = tr[xx^TA] \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial A} tr[AB] = B^T \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial A} log |A| = A^{-T} \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial A} x^TAx = xx^T $$

The derivative of the log likelihood with respect to $\sum^{-1}$ is given by

$$ \frac{ \partial L }{\partial \sum^{-1}} = \sum_{i=1}^N \frac{1}{2} \sum - \frac{1}{2} (x_i - \mu) (x_i - \mu)^T $$ Thus,

$$ \sum_{ML} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N (x_i - \mu) (x_i - \mu)^T $$

Discriminal vs Generative Models

Take the problem mentioned in the introduction as an example, suppose we have 2 classes, ‘cat’ and ‘dog’, and we want to know which class the new image belong to. The problem is to find the probability $P(C=cat|x)$ and $P(C=dog|x)$, and then we classify the image into the class with the largest probability.

Usually, we think of our observations as given and the predictions as random variables, and we model the target variable as a function of the predictors. This is known as discriminal model. In this example, we could use logistic regression to make a classification, and the corresponding probability can be computed using a sigmoid function

$$ P(C=cat|X)=\frac{1}{1 + e^{-(wx + b)}} $$

However, we can also consider both features and target variables at the same time. Using the Bayes' rule below, we can calculate $P(Y|X)$ in another way,

$$ P(C=cat|X) \propto P(X, C=cat)= P(X|C=cat)P(C=cat) $$

This is known as generative model, where we use Bayes' rule to turn $P(X|Y)$ into $P(Y|X)$.

In discriminal model, we don’t need the prior of classes, so there are less parameters to be determined. Also, it might have a better performance if the estimate for that prior is far away from the true distribution.

Graphical Models

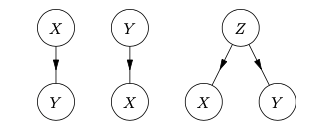

Given 2 random variables, $X$ and $Y$, they could be dependent directly or not. Even if they are not dependent directly, typically there is still correlation between them. If they are correlated, then

- X could affect Y

- Y could affect X

- X has no direct effect on Y, but they could be both affected by another random variable Z

We can describe the above relationships using a graph, where each node represents a random variable and the links between nodes show that relationship. The above three relationships are captured by the following figure,

Such a graph is known as Bayesian networks where we use a directed graph to show causal relationships between random variables. Specifically, we add directed links between $X$ and $Y$ if $X$ directly influences $Y$ shown in the left graph of Figure 1.

Conditional Independence

The left and middle graphs of Figure 1 are easy to understand since they only have two variables, and they are denoted by $P(Y|X), P(X|Y)$ respectively. However, the last one with three variables, $X, Y, Z$, is a bit tricky. Let’s first consider the conditional distribution of $X$ given Z and Y, we have

$$ P(X|Z, Y) = P(X|Z) $$

If we further consider the joint distribution of X and Y conditioned on Z, then we have

$$ P(X, Y|Z) = \frac{P(X, Y, Z)}{P(Z)} = \frac{P(Z) P(Y|Z)P(X|Z, Y)}{P(Z)} = P(X|Z)P(Y|Z) $$

This is called conditional independence, which means that X and Y are statistically independent, given Z. From the view of a graphical model, we can see that there is no direct link between X and Y shown in the right graph of Figure 1.

Latent Dirichlet Allocation

Now let’s learn a topic modeling method that utilises the knowledge we’ve talked about so far, Latent Dirichlet Allocation(LDA). Note this is not linear discriminant analysis, which is also abbrivated to LDA. Here, LDA is an unsupervised learning method that is used to model topics within a set of documents. Speaking of ‘topic’, it means that when you find a group of words occuring many times in an article, such as ‘banana, apple, fruit, vegetable’, you will relate them to an area, like ‘Food’ in this case.

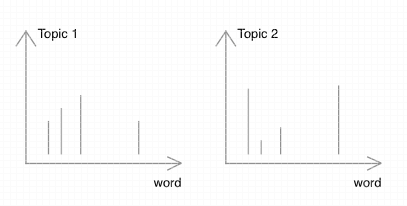

Latent

In LDA, documents are represented as a fixed group of topics, which are unknown as latent variables. And these topics are characterized by a small specific set of words. For example, words like ‘teacher, student, school, exam, marks’ should occur more frequently in the area of Education than topics like Sports. This means different topics have different word distribution, as shown in Figure 2.

If a document contains more words like ‘teacher, school’, it’s likely to be identified as ‘Education’. But it could contain other topics. For example, if this is a document regarding a sports contest held in a school, then it’s much likely to be associated with ‘Sports’ rather than ‘Education’. Thus, we can see that a document can also contain different topics with different weights, i.e. each document has its own topic distribution.

From above, we know that a document consists of a group of topics, and each topic has its special words. To generate a document, we can randomly choose N topics for N words in a document and then randomly choose a word from the corresponding topic. Of course, such an article contains little meaning since we ignore the order and semantics of words. But it’s reasonable for LDA since LDA treats documents just as a bag of words(BOW).

Dirichlet

So the topic-word distribution and doc-topic distribution are the unknown parameters we want to find, but there are many possible values for them. Again, we need a right prior to describe this uncertainty of the values, but which prior should we use?

Remember that we draw a topic from $K$ topics for each word in a document with $N$ words, it means there are $K$ possbile outcomes available for each word, and we repeat this process $N$ times, so it’s a multinominal distribution. And this is true for drawing a word from that topic with $V$ words. Furthermore, we’ve known that the cojugate prior of the multinominal distribution is Dirichlet distribution, so Dirichlet distribution is chosen as our prior, where

- doc-topic distribution follows $\theta^d \sim Dir(\alpha)$

- topic-word distribution follows $\phi^t \sim Dir(\beta)$

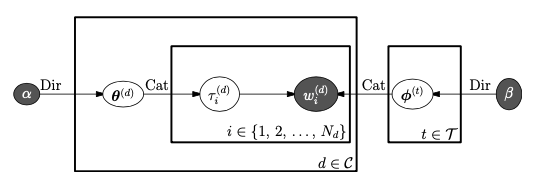

Allocation

To sum up, the whole process of generating a document in LDA is illustrated in Figure 3,

The figure looks a bit scary, well, let’s start with some notations first,

- $M=|D|$, the number of documents

- $D={d_1, d_2, …, d_M}$, where $d_i$ represents $i_{th}$ document

- $V=|W|$, the number of vocabulary appeared in all documents

- $W={w_1, w_2, …, w_V}$, where $w_i$ represents $i_{th}$ word

- $K = |T|$, the number of topics

- $T={t_1, t_2, …, t_K}$, where $t_k$ represents $k_{th}$ topic

- $N_{d}$, the number of words in a document $d$

- $\bold w^{d}={w_1^{d}, w_2^{d}, …, w_{N_{d}}^{d}}$, where $w_i^{d}$ represents $i_{th}$ word in a document $d$

- $\theta^d$ is a probability vector, which represents the distribution of topics in a document $d$

- $\Theta = (\theta^d|d \in D)$

- $\phi^t$ is a probability vector, which represents the distribution of words associated with a topic $t$

- $\Phi = (\phi^t|t \in T)$

- $\bold t^{d} = t_1^{d}, t_2^{d}, …, t_{N_{d}}^{d}$, where $t_i^{d}$ represents a topic drawn from $\theta^d$

From Figure 3, the joint distribution of the hidden and observed variables for a single document is given by,

$$ p(\bold t^d, \bold w^d, \theta^d, \Phi|\alpha, \beta) = P(\theta^d|\alpha) P(\Phi|\beta) P(\bold t^d, \bold w^d|\theta^d, \Phi) = P(\theta^d|\alpha) P(\Phi|\beta) \prod_n^{N_d} P( t_n^d, w_n^d|\theta^d, \Phi) $$

$$ = P(\theta^d|\alpha) P(\Phi|\beta) \prod_n^{N_d} P(t_n^d |\theta^d, \Phi) P(w_n^d|t_n^d, \theta^d, \Phi) $$

$$ = P(\theta^d|\alpha) P(\Phi|\beta) \prod_n^{N_d} P(t_n^d|\theta^d) P(w_n^d|\phi^{t_n^d}) $$

$$ = P(\theta^d|\alpha) \prod_t^TP(\phi^t|\beta) \prod_n^{N_d} P(t_n^d|\theta^d) P(w_n^d|\phi^{t_n^d}) $$

Our goal is to maximise this equation, but before that we need to eliminate the hidden variable $\bold t^d$,

$$ p(\bold w^d, \theta^d, \Phi|\alpha, \beta) = \int_{t^d} P(\theta^d|\alpha) P(\Phi|\beta) \prod_n^{N_d} P(t_n^d|\theta^d) P(w_n^d|\phi^{t_n^d}) $$

$$ = P(\theta^d|\alpha) P(\Phi|\beta) \prod_n^{N_d} \sum_{t_n^d=t_1}^{t_K} P(t_n^d|\theta^d) P(w_n^d|\phi^{t_n^d}) $$

There are two common ways to compute this: Gibbs sampling and variational inference.

Gibbs Sampling

TODO

Variational inference

TODO