Recommender Systems

Recommender system is one of the most popular studying fields in machine learning due to its wide application in our daily life. When you shop online, such as Amazon, you can see similar items just below the item you are looking at. The goal of a recommender system is to make recommendations that fit the user’s taste. In this post, we will go through the very basic concepts and several classcial techniques in the field of recommender systems.

Overview

Recommendations can be classified as two categories, as Figure 1 shows,

- non-personalised

- recommendations are the same for all users

- e.g. the most popular movies, the top ten hotels, …

- personalised

- recommendations vary by users

Obviously, we focus on the latter one. The mainstream algorithms includes

- content-based filtering

- recommend items based on the attribtues of items, users, or both (feature engineering)

- e.g. when you buy the novel “The ABC Murders “, the system will also recommend other novels written by Agatha Christie to you.

- collaborative filtering

- employ the wisdom of the crowd instead of extracting good attributes manually

There are three main types of collaborative algorithms, namely,

- user-based filtering

- item-based filtering

- matrix factorisation

Data

Data is all we need. Figure 2 shows that a recommender system needs three types of data,

- items data

- user data

- the interaction between items and users

Each type of data has its own properties. Items like clothes have attributes of size and colour. Users have age and gender. The interactions between items and users include contextual attributes, such as weather, geographical location, day of the week, and so on.

Item Content Matrix (ICM)

As mentioned earlier, items have attributes. Mathematically, we can describe that relation using Item Content Matrix or ICM, where each row indicates an item and each column represents an attribute. The value of ICM usually is 1 or 0. If an item contains a specific attribute listed in ICM, the corresponding cell will be set to one, zero otherwise. But you can also set a value between 0 and 1 to describe the importance of that attribute or other numerical values for quantitative variables like year.

User Rating Matrix (URM)

Similarly, the opinions of users on items are described mathematically through the User Rating Matrix or URM. Each row represents a user, and each column represents an item. If we have no idea the opinion of someone on an item, the corresponding value is missing (when computing, you can treat it as zero).

Implict Ratings

Ratings can be implicit or explicit. Implicit ratings are deduced by looking at how you interact with the system, for instance, the time-on-page, the viewing time of a movie, clicks, purchases, and so on. If one stops watching a movie after 10 minutes, we assume that that user does not like that movie. However, one may have to stop watching a film because of an important call.

Explict Ratings

Explicit ratings are done by asking users to rate items on a rating scale, for example, five stars for Educated. However, designing a rating scale is not an easy thing. It depends on your application, customers, and so on. As shown in the following table, a smaller and odd rating scale is generally preferable due to its simplicity and variety. In practice, we always see a one-to-five rating or ‘like/dislike’ buttons at almost every website that needs to collect users' opinions.

| Large rating scale | Smaller rating scale | Even rating scale | Odd rating scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| complex and requires more effort | easy to understand | either negative or positive ratings, forcing people to express their opinions | introduces the neutral rating, which makes people feel more comfortable |

| fewer ratings | more ratings | fewer ratings | people tend to choose the neutral rating unless they have a strong positive or negative opinion |

Non-personalised recs

Top 10

As we said before, the top 10 perhaps is the most common type of non-personalised recs. You can see Top 10 everywhere on the Internet.

Method 1: Top Popular

An intuitive method to get the top 10 items is to order items by the number of users that have bought, seen, or given their opinions.

# top 10 movies

movies_has_seen = Log.objects.values('content_id').filter(event='seen').annotate(Count('user_id'))

sorted_items = sorted(movies_has_seen, key=lambda item: -float(item['user_id__count']))

sorted_items[:10]

Method 2: The Best Rated Items

Another technique is to calculate the average rating for each item and retrieve the top 10 items ranked by the average rating in descending order.

movies_avg_rated = Rating.objects.values('movie_id').annotate(Avg('rating'))

sorted(movies_avg_rated, key=lambda item: -float(item['rating__avg']))[:10]

To calculate the average rating, we need the help of URM. Let $r_{ui}$ be the non-zero rating given by user $u$ to item $i$, and $N_i$ be the number of users who rated item $i$, then the average rating of item $i$ is given as

$$ b_i = \frac{\sum_u r_{ui} }{N_i} $$

Market Basket Analysis

Apart from the “Top 10”, another type of recommendations also appears often when you look at an item at Amazon. That is “Frequently Bought Together (People who bought this item also bought)”. Basically, this kind of recommendations are based on association rule analysis (market basket analysis), which is a technique widely used by retailers to discover associations between items. They want to know what items are frequently bought together so that they can place them in a similar manner.

Let $I = { I_1, I_2, …, I_m }$ be the items and $T = { t_1, t_2, .., t_N }$ a list of transactions.

Rule

Association rules can be written in the form of “IF-THEN”, $$ \{{ A \}} \rarr \{{ B \}} $$ where $A \sub I$, $ B \sub I$, and $A \cap B = \empty$. The above rules means that if a customer buys $A$, then he is likely to buy $B$. A and B can include many items, $$ \{{\text{bread},\text{milk}\}}\rarr\{{\text{carrots},\text{yogurt}\}} $$

Support

Support tells us how frequently A and B appear together by calculating the fraction of transactions that contains A and B.

$$ \text {supp} (A \rarr B) = \frac{|A \cup B|}{|T|} $$ Thus, we can filter out the item sets that occur less frequently by setting a minimum support.

Confidence

Confidence shows the percentage in which B is bought with A.

$$ \text {conf} (A \rarr B) = \frac{\text{supp}(A \rarr B)}{\text{supp}(A)} $$

Lift

Lift indicates the strength of a rule.

$$ \text {list} (A \rarr B) = \frac{\text{supp}(A \rarr B)}{\text{supp}(A)\text{supp}(B)} $$

With these terms, now we can make an association analysis using the Apriori algorithm.

data = {

'1': [1,0,1,0],

'2': [0,1,1,1],

'3': [1,1,1,0],

'4': [1,0,0,0],

'5': [0,1,1,1]

}

index = [ 'InvoiceNo_' + str(i) for i in range(4) ]

basket_set = pd.DataFrame(data=data, index=index)

freq_itemsets = apriori(basket_set, min_support=0.5, use_colnames=True)

freq_itemsets['length'] = freq_itemsets['itemsets'].apply(lambda x: len(x))

freq_itemsets

# 0.25 (4) 1 # since 0.25 < 0.5, so it's not included.

support itemsets length

0 0.50 (1) 1

1 0.75 (2) 1

2 0.75 (3) 1

3 0.75 (5) 1

4 0.50 (3, 1) 2

5 0.50 (2, 3) 2

6 0.75 (2, 5) 2

7 0.50 (3, 5) 2

8 0.50 (2, 3, 5) 3

association_rules(freq_itemsets, metric='confidence', min_threshold=0.75)

antecedents consequents antecedent_support consequent_support support confidence lift

(1) (3) 0.50 0.75 0.50 1.0 1.333333

(2) (5) 0.75 0.75 0.75 1.0 1.333333

(5) (2) 0.75 0.75 0.75 1.0 1.333333

(2, 3) (5) 0.50 0.75 0.50 1.0 1.333333

(3, 5) (2) 0.50 0.75 0.50 1.0 1.333333

PS: Here is the complete code.

Similarity

Before introducing the personalised recs, we should be familiar with similarity. There are many ways to measure similarity or distance between two vectors, for example,

- Jaccard Distance

- Mahantan Distance

- Euclidean Distance

- Cosine Similarity

- Pearson Correlation Coefficient

- K-means clustering

Cosine Similarity

Cosine similarity between users is defined as,

$$ S_{uv} = \frac{r_u \cdot r_v}{||r_u|| * ||r_v||} $$

where $r_u$ is the $u_{th}$ row of URM.

Adjusted Cosine Similarity

On the other hand, we should notice is that people use different rating scales. For example, Alice is generous to rating while Bob is a bit harsh on it, so a rating of 3 in Bob is equivalent to 5 in Alice. To deal with this, we normalise the ratings by subtracting the user’s average rating, denoted by $\overline r_u$, as follows,

$$ S_{uv} = \frac{(r_u - \overline r_u) \cdot (r_v - \overline r_v)}{||r_u - \overline r_u|| * ||r_v - \overline r_v||} $$

Pearson Correlation Coefficient

The above formula is the same as Pearson Correlation Coefficient. The only difference between them is that the Pearson only works for vectors with the same size (the rated items in common between users), while the adjusted cosine similarity considers all items by treating missing values as zero.

For instance, below are the ratings of Alice and Bob for six films.

Alice: [4, 5, 4, NaN, 3, 3]

Bob: [3, 3, 3, 2, 4, 5]

Step 1: calculating the average rating

- Alice: $(4+5+4+3+3)/5 = 3.8$

- Bob: $(3+3+3+2+4+5)/6= 3.33$

Step 2: Normalising ratings

- Adjusted Cosine

Alice: [0.2, 1.2, 0.2, -3.8, -0.8, -0.8]

Bob: [-0.33, -0.33, -0.33, -1.33, 0.67, 1.67]

Notice that we treat $NaN$ as $0$.

- Pearson

Alice: [0.2, 1.2, 0.2, NaN, -0.8, -0.8]

Bob: [-0.33, -0.33, -0.33, -1.33, 0.67, 1.67]

Step 3: Calculating similarity

- Adjusted Cosine

$$ \frac{0.2*-0.33+1.2*-0.33+0.2*-0.33+ -3.8*-1.33 +-0.8*0.67+-0.8*1.67}{\sqrt{0.2^2+1.2^2+0.2^2+ -3.8^2+-0.8^2*2} \sqrt{-0.33^2*3+-1.33^2 + 0.67^2+1.67^2}} \\ = -0.62 $$

- Pearson

$$ \frac{0.2*-0.33+1.2*-0.33+0.2*-0.33+-0.8*0.67+-0.8*1.67}{\sqrt{0.2^2+1.2^2+0.2^2+(-0.8)^2+(-0.8)^2} \sqrt{-0.33^2 + -0.33^2+-0.33^2+0.67^2+1.67^2}} \\ = -0.75 $$

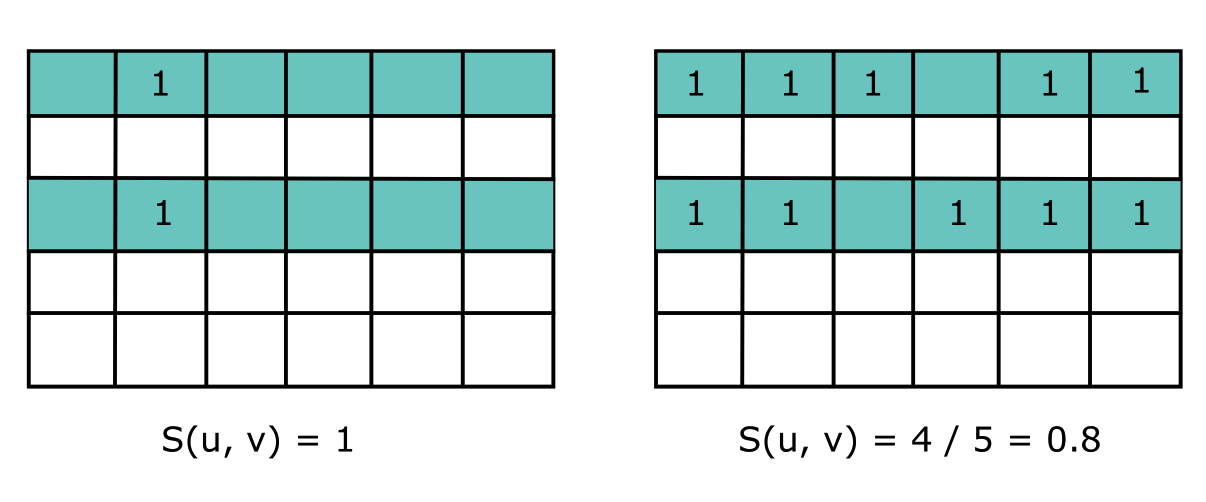

Overlapping

However, the cosine similarity is not perfect enough. Figure 3 shows that the similarity between the users who rated one item only is greater than those who have more items in common. However, the result is not convincing because there are less common in the first pair of users. In other words, the similarity is not reliable when the support is small. The support is the number of non-zero ratings of a user.

3

So how to solve it? We add a shrink term $C$ to the denominator of the cosine to reduce the magnitude of the cosine similarity

$$ S_{uv} = \frac{r_u \cdot r_v}{||r_u|| * ||r_v|| + C} $$

Alternatively, you can also set a threshold for the minimum support to filter out the users who have rated only one or two items. The codes below return the number of overlapping elements between users. On the contrary, if there are too many overlapping users, users are so alike that it’s difficult to recommend special items (the recommendations are too general).

overlap_matrix = URM.astype(bool).astype(int)

overlap_matrix = overlap_matrix @ overlap_matrix.T

Neighborhood

In practice, we only consider a small set of similar users or items, which is called as the neighborhood of the target user or item.

Cluster

Clustering is one technique to divide data into several similar groups, so the neighborhood of a user is the group that he belongs to. However, clustering has some drawsbacks, e.g. sensitive to the shape of data.

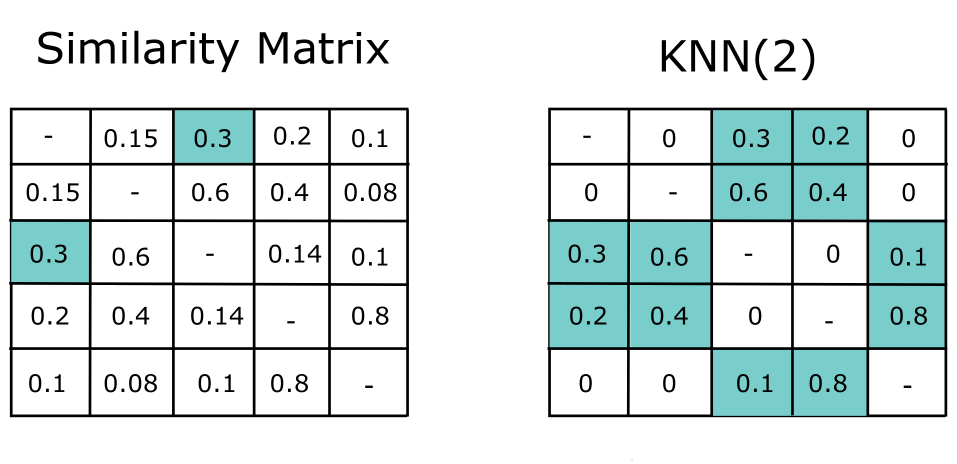

KNN

We have introduced KNN before. In the case of recs, for example, $K=2$ means that we only keep the most two similar items for each column.

Threshold

Another simple way is to set a threshold for similarity. The figure below illustrates the difference between KNN and threshold.

![[Source: Practical Recommender Systems]](/blog/post/images/topn-threshold.png#full)

Content-based Filtering

Now we focus on personalised recs. We first look at content-based filtering, which is the first strategy applied in recommendations. As its name suggests, it relies on the metadata of the items without using any opinion of others, as Figure 5 shows.

![Figure 5: Example of content-based recommendation pipeline. [Source: Practical Recommender Systems]](/blog/post/images/example-content-filter.png#full)

The core of content-based filtering is to make recommendations based on the attributes of the content. However, not all attributes are useful and equally important. Besides, some features may not be explicitly visible to us. Thus, we need to extract knowledge from the content and select features carefully.

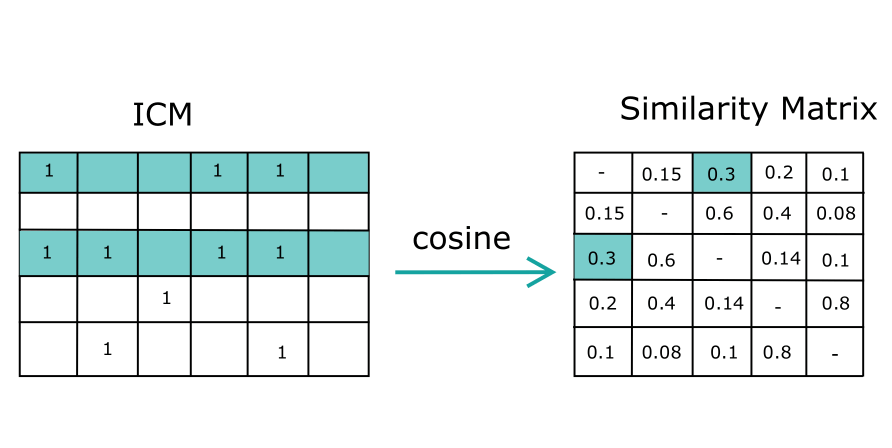

Similarity

We first find similarity between items by applying cosine similarity to ICM, as shown in Figure 6.

The cosine similarity is defined as, $$ S_{ij} = \frac{\overrightarrow I_i \cdot \overrightarrow I_j}{||\overrightarrow I_i|| * || \overrightarrow I_j||} $$ where $I_j$ indicates the $j_{th}$ item (row) in ICM.

TF-IDF

As mentioned previously, attributes are not of equal importance, so it’s essential to know what features are more important and do feature selections to improve performance. TF-IDF is a technique used to analyse the importance of something like a word in NLP. In the case of ICM, we consider each item as a document and each column as a word. Suppose we want to know the importance of an attribute, say $a$, then TF and IDF are calculated as follows,

$$ TF_{a, i} = \frac{|I_{ai}|}{|I_i|} \\ IDF_{a} = - \text{log} \frac{|a \in I|}{|I|} $$

where

- $I_{ai}$ is the number of $a$ appearing in the item $i$; often equal to 1

- $I_i$ represents the number of attributes of item $i$

- $|a \in I|$ is the number of items containing attribue $a$

- $|I|$ is the total number of items

LDA

Pros and Cons

Pros

- You can always get recommendations even if it’s your first visit

- It recommends across popularity; that is, it does not care about the popular items now

Cons

- The system is less likely to recommend new or surprising items

- Limited understanding of content; it’s likely to misunderstand what the customers like

Collaborative Filtering

User-based

User-based filtering works on the idea that we look for users with a similar taste and recommend the items they like most. So there are two questions here

- How to measure similarity between users? (See above)

- What to recommend to the target user? Two common ways,

- Average

- Vote

With similarity matrix, we make a prediction for item $i$, given the user $u$

$$ \hat r_{ui} = \overline r_u + \frac{\sum_{v \in KNN(u)} S_{uv} (r_{vi} - \overline r_v)}{\sum_{v \in KNN(u)} S_{uv}} $$

So, user-based CF calculates a weighted average rating of several nearest neighbours of user $u$ for item $i$.

Item-based

Likewise, the prediction using item-based CF is given as,

$$ \hat r_{ui} = \overline r_u + \frac{\sum_{j \in KNN(i)} S_{ij} (r_{uj} - \overline r_u)}{\sum_{j \in KNN(i)} S_{ij}} $$

where the adjusted $S_{ij}$ is defined as

$$ S_{ij} = \frac{\sum_u (r_{ui} - \overline r_u) (r_{uj} - \overline r_u) }{ \sqrt{\sum_u(r_{ui} - \overline r_u) ^2} \sqrt{\sum_u(r_{uj} - \overline r_u) ^2}} $$

Pros and Cons

Pros

- It does not need metadata about the content

Cons

-

cold start

- What items to recommend to a new user?

- How to recommend a new item to users?

-

sparse URM $$ \text {sparsity} = 1 - \frac{|R|}{|U||I|} $$

-

scaling can be challenging for growing datasets.

Matrix Factorisation

Unlike user-based CF and item-based CF, matrix factorisation aims to factorise URM into two matrices. Basically, this technique tries to find the latent factors underlying the interactions between users and items. Technically speaking, SVD and Funk SVD are two common methods to achieve this goal. They look alike at first sight but are different things.

SVD

We’ve known that any matrix can be decomposed into three matrices as shown below,

$$ A = U\Sigma V^T $$ where

- $U^{m \times k}$ - User factor matrix

- $\Sigma^{k \times k}$ - Diagnoal matrix

- $V^{n\times k}$ - Item factor matrix

As we know, $\Sigma$ contains singular values, which are sorted from the largest to the smallest. These values indicate the weight of the factor $k_i$, so we can remove some unimportant features by setting the corresponding singular value to zero. That’s called truncated SVD. Besides, reducing the matrix also saves memory space. From Figure 7 we can see that zero sigular values will remove the right-most columns of $U$ and the bottom-most rows of $V^T$.

For coders, below are PyTorch implementation of SVD.

U, S, V = torch.svd(A)

S[-1] = 0

A_hat = U @ torch.diag(S) @ V.T

However, there are some obvious problems with SVD. First, it’s time-consuming to calculate large matrixes. Second, we have to impute the missing values first. Usually, we impute zero cells with user’s average rating. Nevertheless, SVD is not very computationally efficient.

Funk SVD

The idea of Funk SVD proposed by Simon Funk is to compute the lower-rank approximation of a matrix by minimising the squared error loss. The difference wih SVD above is that Funk SVD only considers the known values, which means we discard the missing values in URM. Mathematically, the goal of Funk SVD is to minimise the following loss function,

$$ \text{min}_{p, q} \sum_{(u, i) \in K} \epsilon_{ui}^2 = \text{min}_{p, q} \sum_{(u, i) \in K} (r_{ui} - p_u q_i)^2 $$

where

- $p_u$ is the $u_{th}$ row of the user factor matrix $U$

- $q_i$ is the $i_{th}$ column of the iterm factor matrix $Q$

- $r_{ui}$ is the rating of the item $i$ given by the user $u$

- $K$ is the set of all known ratings

To find the solution, we first compute the derivative of $L$ w.r.t $p_u$ and $q_i$, respectively, and then use stochastic gradient descent to arrive at the minimum point. $$ p_u \larr p_u + lr * \epsilon_{ui} q_i\\ q_i \larr q_i + lr * \epsilon_{ui} p_u $$

def sgd_factorise(A: torch.Tensor, rank: int, num_epochs=1000, lr=0.01) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

m, n = A.shape

U = torch.rand((m, rank))

V = torch.rand((n, rank))

for i in range(num_epochs):

for r in range(m):

for c in range(n):

e = A[r, c] - U[r] @ V[c].T

U[r] = U[r] + lr * e * V[c]

V[c] = V[c] + lr * e * U[r]

return U, V

Regularization

Alternatively, we can add regularization to Funk SVD to avoid large parameters (overfitting).

$$ \text{min}_{p, q} \sum_{(u, i) \in K} \epsilon_{ui}^2 + \beta (||P||^2 + ||Q||^2) $$ Now the updated rules are

$$ p_u \larr p_u + lr * (\epsilon_{ui} q_i - \beta p_u) \\ q_i \larr q_i + lr * (\epsilon_{ui} p_u - \beta q_i) $$

Bias

Finally, we need to consider the bias or intercept. As mentioned earlier, people have their own criterions from rating (user bias) and some items are naturally highly expected (item bias). So, the new predicted rating is defined as

$$ \hat r_{ui} = p_u q_i + \mu + b_u + b_i $$

where $\mu$ is the global average raing, $b_u$ is the user bias, and $b_i$ is the item bias. Thus, the final loss function is defined as follows,

$$ \text{min}_{p, q} \sum_{(u, i) \in K} \epsilon_{ui}^2 + \beta (||P||^2 + ||Q||^2 + ||b_u||^2 + ||b_i||^2) $$

The derivatives of $L$ w.r.t $b_u, b_i, p_u, q_i$ are

$$ b_u += \lambda (\epsilon_{ui} - \beta b_u) \\ b_i += \lambda (\epsilon_{ui} - \beta b_i) \\ p_u \larr p_u + lr * (\epsilon_{ui} q_i - \beta p_u) \\ q_i \larr q_i + lr * (\epsilon_{ui} p_u - \beta q_i) $$

Cold Start

Evaluation

Baseline Predictors

Quality Indicators

Relevance、 Coverage、Novelty、Diversity、Consistency、Confidence、Serendipity

Metrics

Online Evaluation

Direct user feedback

- ques should be meaningful and non–biased

- opinion not reliable

A/B test

- monitoring user behavior

- difficult to set up

- result might be difficult to interpret

Controlled experiments

Crowdsourcing

Offline evaluation

References

- Apriori Algorithm: Know How to Find Frequent Itemsets

- Market Basket Analysis

- Recommender Systems Specialization

- Singular Value Decomposition vs. Matrix Factorization in Recommender Systems

- Matrix Factorization: A Simple Tutorial and Implementation in Python

- Recommender system: Using singular value decomposition as a matrix factorization approach